This Blog Post Could Save A Life

Hiking in remote areas comes with inherent risks, making basic wilderness first aid knowledge an essential skill for handling medical emergencies. This guide outlines the key principles that every hiker should understand to assist an injured person on the trail and ensure safety for all. However, this guide is not meant as a replacement for formal wilderness first aid training.

Why Hikers Need Wilderness First Aid

Hiking often takes individuals into remote and unpredictable environments where professional medical assistance may be hours or even days away. In these situations, wilderness first aid knowledge is not just beneficial—it can be lifesaving.

Injuries such as sprains, fractures, cuts, or more severe conditions like heatstroke and hypothermia can occur rapidly. Without the right skills, a minor issue can escalate into a serious emergency. Rough terrain, extreme weather conditions, and limited access to communication present additional challenges, making it crucial for hikers to know how to assess injuries, stabilize patients, and prevent complications.

Wilderness first aid also fosters a culture of safety and preparedness within the outdoor community, allowing hikers to assist each other effectively in emergencies.

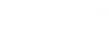

READ: Building a first aid kit

Wilderness First Aid Certifications

For those looking to enhance their preparedness, several wilderness first aid certifications are available:

- Wilderness First Aid (WFA): A basic course covering essential first aid skills for backcountry settings. Typically a two-day course, it is ideal for casual hikers and outdoor enthusiasts.

- Wilderness First Responder (WFR): A more in-depth certification designed for guides, outdoor educators, and serious adventurers. This course typically lasts 5-10 days and covers more advanced medical scenarios and patient care.

- Wilderness Emergency Medical Technician (WEMT): A professional-level certification for those wanting to combine wilderness medicine with emergency medical technician (EMT) training. This course prepares individuals to handle complex medical emergencies in remote settings.

Scene Size Up - Staying Safe

When you encounter an injured individual in the wilderness, the first and most crucial step is to conduct a thorough scene size-up. This involves carefully evaluating the environment around you to identify any potential hazards that could put you or the injured person in further danger. Remember, if you are injured, you may exacerbate the situation rather than remedying it.

Begin by assessing the terrain. Look for signs of instability, such as loose rocks, muddy areas, or cliffs that could cause further injury or complicate your rescue efforts. Steep inclines or uneven ground may make it challenging to move the injured person safely, so ensure the path to them is secure before proceeding.

Next, take note of any falling debris. In forested areas, branches or trees might be weakened or already damaged from storms, posing a risk of falling when disturbed. If you’re in a rocky area, there may be loose rocks or unstable formations that could shift unexpectedly.

Wildlife threats should also be considered. In remote wilderness areas, animals like bears, snakes, or even smaller creatures like insects can pose risks, particularly if the injured individual is in a vulnerable position or if you’re unable to quickly remove them from the area. Keep an eye out for signs of animal presence, such as tracks, droppings, or animals themselves.

By ensuring your own safety first, you are better equipped to approach the situation with a clear mind and act decisively. Taking the time to evaluate these factors reduces the risk of becoming a victim yourself and sets the stage for providing the most effective assistance to the injured person. Safety for both you and the person you’re helping is always the first priority.

Introductions, Consent, and Implied Consent

Once the scene is safe, introduce yourself and obtain the individual’s consent before administering aid. Clear communication is vital. If the person is unconscious and unable to respond, implied consent applies. This means that in a life-threatening emergency, it is assumed that the individual would want assistance if they were able to communicate their wishes. This legal and ethical principle ensures that necessary medical aid can be provided without delay.

Airway, Breathing & Circulation

When responding to a medical emergency, the ABCs—Airway, Breathing, and Circulation—are the first and most critical factors to assess. These fundamental checks help determine whether an individual is in immediate danger and guide your first aid response. Addressing life-threatening conditions related to the ABCs before moving on to further assessment can mean the difference between life and death.

A – Airway

The first step is to make sure the person’s airway is open and unobstructed. If the airway is blocked, oxygen cannot reach the lungs, leading to rapid deterioration.

- If the individual is conscious, ask them to speak. If they can talk clearly, their airway is likely open.

- If they are unconscious, check for obstructions by looking inside the mouth and throat. Common blockages include the tongue (which may fall back and obstruct airflow in an unconscious person), food, vomit, or foreign objects.

- If needed, perform a head tilt-chin lift maneuver (for non-trauma cases) or a jaw thrust (if a spinal injury is suspected) to open the airway. Remove any visible obstructions carefully.

B – Breathing:

Once the airway is open, check if the individual is breathing normally. Lack of oxygen for even a few minutes can lead to irreversible brain damage.

- Look, listen, and feel for breathing:

- Look for chest rise and fall.

- Listen for air movement.

- Feel for breath on your cheek.

- If they are breathing normally, monitor their condition and proceed with further assessment.

- If they are not breathing or only gasping, initiate rescue breathing or CPR immediately.

C – Circulation

Circulation refers to the movement of blood throughout the body. A lack of circulation can result from cardiac arrest, severe blood loss, or shock, all of which require immediate intervention.

- Check for a pulse at the carotid artery (neck) or radial artery (wrist).

- Assess for major bleeding, as uncontrolled hemorrhage can quickly become fatal. Apply direct pressure, elevation, and a tourniquet (if necessary) to stop life-threatening bleeding.

- Watch for signs of shock, such as pale or clammy skin, confusion, rapid breathing, or a weak pulse. If shock is suspected, keep the person warm, lay them flat with their legs elevated (unless a spinal injury is suspected), and provide reassurance while awaiting medical help.

By systematically assessing the ABCs, you can quickly identify and address life-threatening conditions, stabilizing the injured person before moving on to secondary assessments and further treatment. This fundamental approach ensures that the most critical survival needs are met first, significantly improving the chances of a positive outcome in a wilderness emergency.

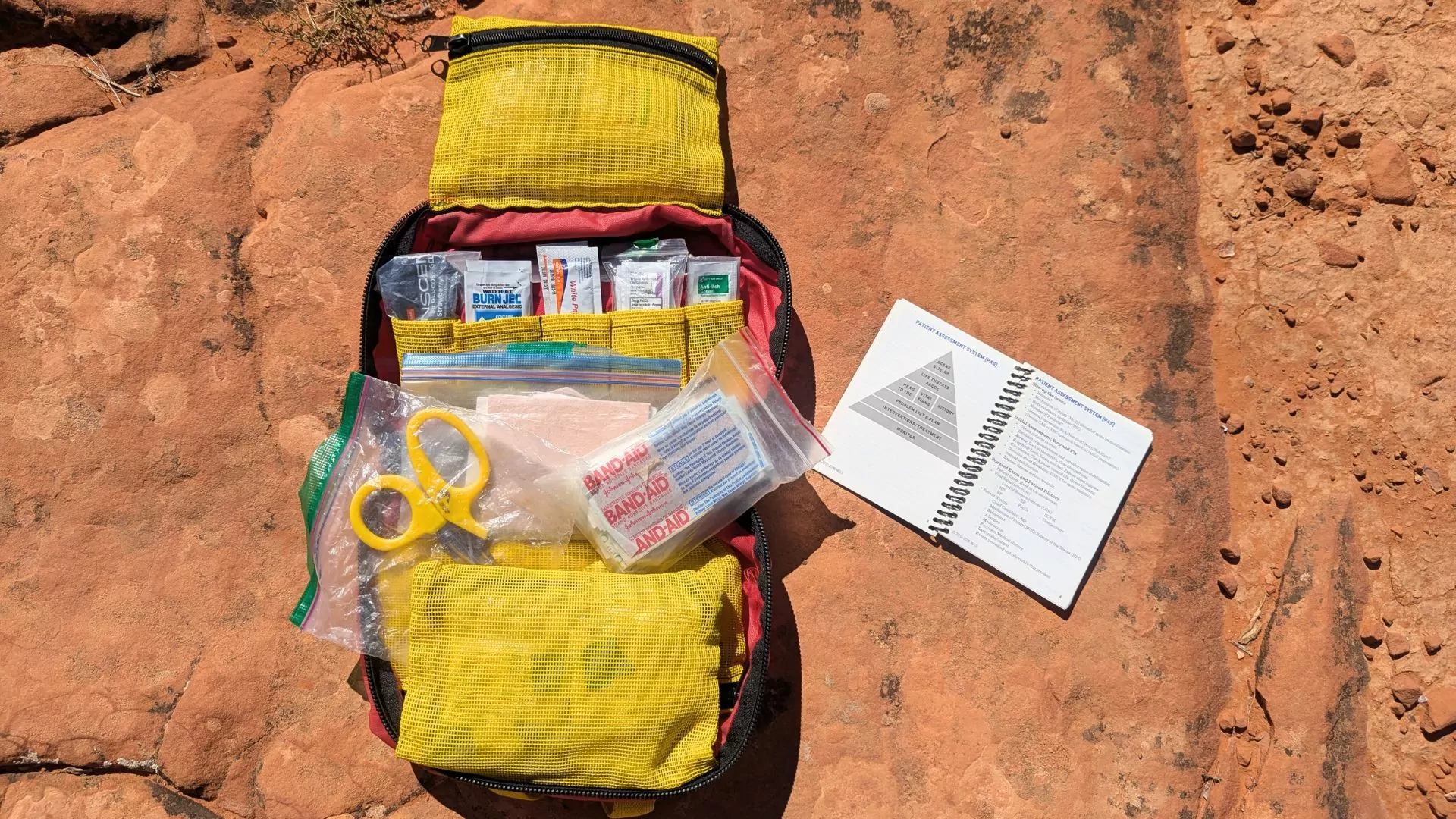

CPR

In emergency situations, particularly when hiking or camping in remote wilderness areas, knowing how to perform CPR (Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) can be the difference between life and death. If a person is found unresponsive and not breathing, immediate action is needed. This is where CPR comes into play.

The first step when encountering an unconscious individual is to assess their responsiveness. Gently shake the person and shout to see if they respond. If there is no reaction, check for signs of breathing. If the individual is not breathing or only gasping, it’s crucial to act quickly by starting CPR.

Performing CPR

- Chest Compressions: Begin by performing 30 chest compressions. Place the heel of one hand in the center of the person’s chest, just below the sternum, and place your other hand on top of the first. Using your body weight, push hard and fast, compressing the chest by at least 2 inches at a rate of 100-120 compressions per minute. This helps circulate oxygenated blood to vital organs, especially the brain and heart, which are most at risk in a cardiac emergency.

- Rescue Breaths: After 30 compressions, give 2 rescue breaths. Ensure the person’s airway is open by tilting their head back and lifting their chin. Pinch the nose shut, cover their mouth with yours, and give a full breath, watching for their chest to rise. If you are unable or unwilling to give mouth-to-mouth breaths, hands-only CPR (just chest compressions) can still be effective in saving a life.

- Continue the Cycle: Continue alternating between 30 compressions and 2 rescue breaths until professional medical help arrives or the person regains consciousness. If the person begins to breathe on their own, check for other signs of life and monitor their condition until help arrives.

Head to Toe Exam

Conduct a thorough and systematic assessment of the injured individual to identify potential injuries and medical conditions. This examination helps determine the extent of harm and guides appropriate treatment. Begin by visually inspecting the entire body, looking for swelling, bruising, deformities, open wounds, or discoloration. Gently palpate (press) different areas to detect hidden injuries that may not be immediately visible. Ask the injured person about any pain, tenderness, numbness, or unusual sensations.

If they are unable to communicate, observe their reactions to touch or movement. Check for responsiveness in extremities by asking them to wiggle fingers and toes. Assess their ability to move joints without pain or restriction. Special attention should be given to the spine, chest, and abdomen, as injuries in these areas can be severe but not immediately obvious.

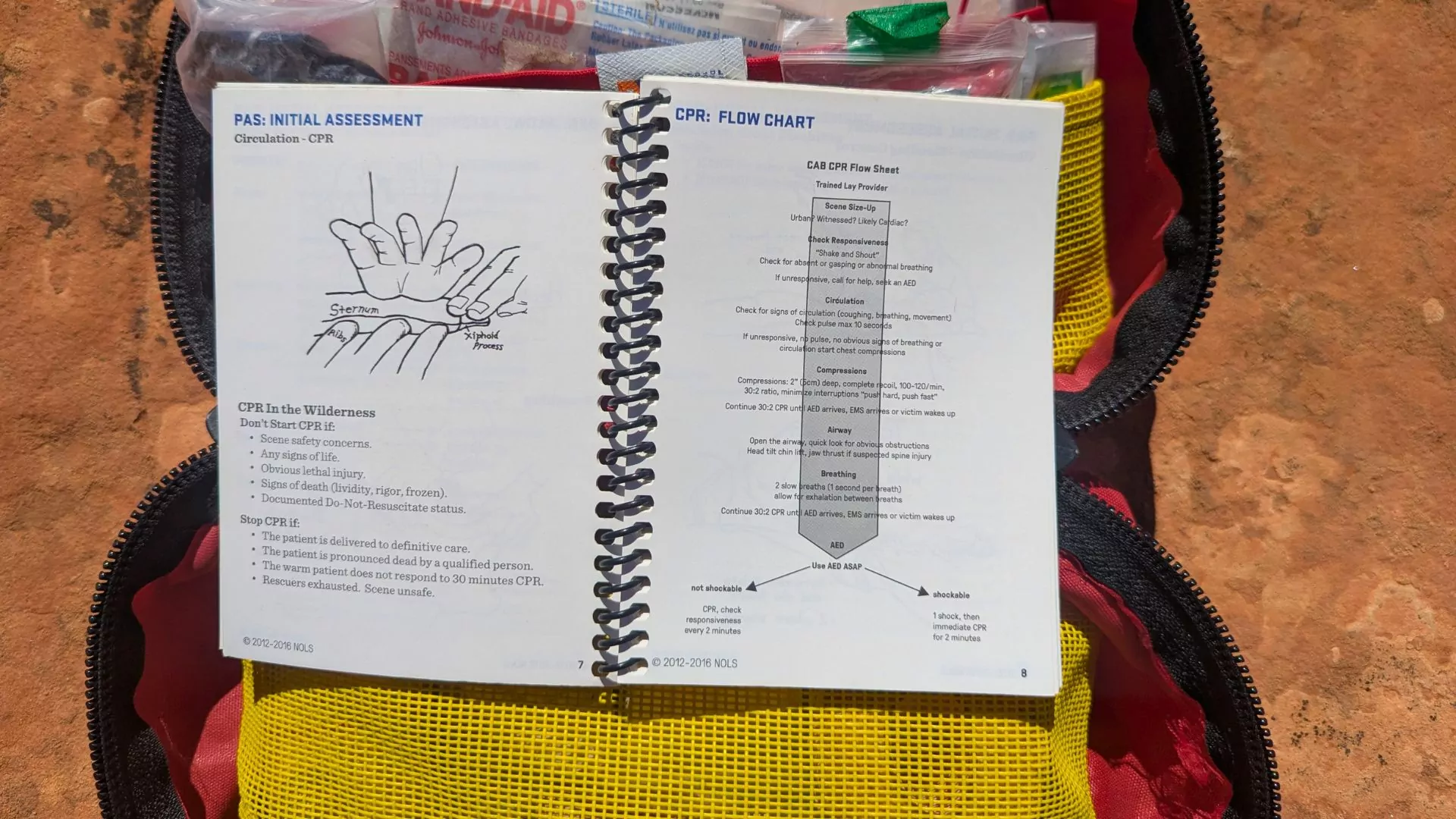

Gathering Background Information

When responding to an emergency in the wilderness, obtaining background information from a conscious injured person is essential. While assessing visible injuries and symptoms is crucial, understanding their medical history, recent activity, and any underlying conditions can provide valuable context that may influence treatment decisions. In remote settings where medical assistance may be hours or even days away, this information helps prevent complications and ensures that care is tailored to the individual’s specific needs.

Key Questions and Why They Matter

Recent Food and Water Intake

- Knowing when the person last ate and drank can help determine if dehydration, heat exhaustion, or low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) is contributing to their symptoms.

- Dehydration is a major concern in the backcountry and can exacerbate shock, heat-related illnesses, and kidney problems.

- If vomiting, diarrhea, or prolonged exertion is involved, knowing their hydration and electrolyte status can guide whether oral rehydration, rest, or urgent intervention is necessary.

Existing Medical Conditions

- Many pre-existing conditions, such as diabetes, asthma, or heart disease, can mimic or worsen injuries and illnesses in the wilderness.

- A diabetic hiker experiencing confusion and weakness may actually be in hypoglycemic shock rather than simply fatigued.

- An individual with a history of seizures may not just be unconscious from trauma but could be experiencing a medical episode.

- Recognizing pre-existing conditions allows rescuers to provide appropriate first aid rather than misinterpreting symptoms.

Allergies

- Allergic reactions, especially anaphylaxis, can be life-threatening and require immediate intervention.

- Common wilderness allergens include bee stings, plant exposure (like poison ivy or oak), and food allergens from snacks or shared meals.

- If an individual carries an EpiPen, it’s critical to locate and administer it if needed.

- Without knowing their allergy history, delayed or incorrect treatment could lead to respiratory failure or shock.

Current Medications

- Some medications can impact the body’s response to injuries or environmental stress.

- Blood thinners (e.g., warfarin, aspirin) increase the risk of severe bleeding from even minor wounds.

- Beta-blockers can affect heart rate and circulation, making it harder to detect shock.

- Insulin or oral diabetes medications can cause dangerous blood sugar swings, requiring careful monitoring.

- If the person is unconscious but carrying medications, checking them can provide critical clues about their medical needs.

Why This Information is Essential

Guides Immediate Treatment – Knowing the person’s history helps differentiate between medical emergencies and environmental stressors, ensuring the right action is taken.

Prevents Complications – Identifying allergies or medication interactions reduces the risk of administering the wrong first aid.

Aids Communication with Medical Professionals – If evacuation or advanced care is needed, relaying this information to rescuers or emergency responders helps them provide faster, more effective treatment.

Increases Survival Chances – In remote environments, where professional medical help may take hours or days, having a clear picture of the person’s health history allows for better long-term care and monitoring.

By gathering background information, you equip yourself with vital details that can mean the difference between effective intervention and worsening conditions. In the backcountry, where resources are limited and medical decisions often need to be made on the spot, this step is just as important as treating visible injuries.

Common Outdoor Injuries and Illnesses

Fractures

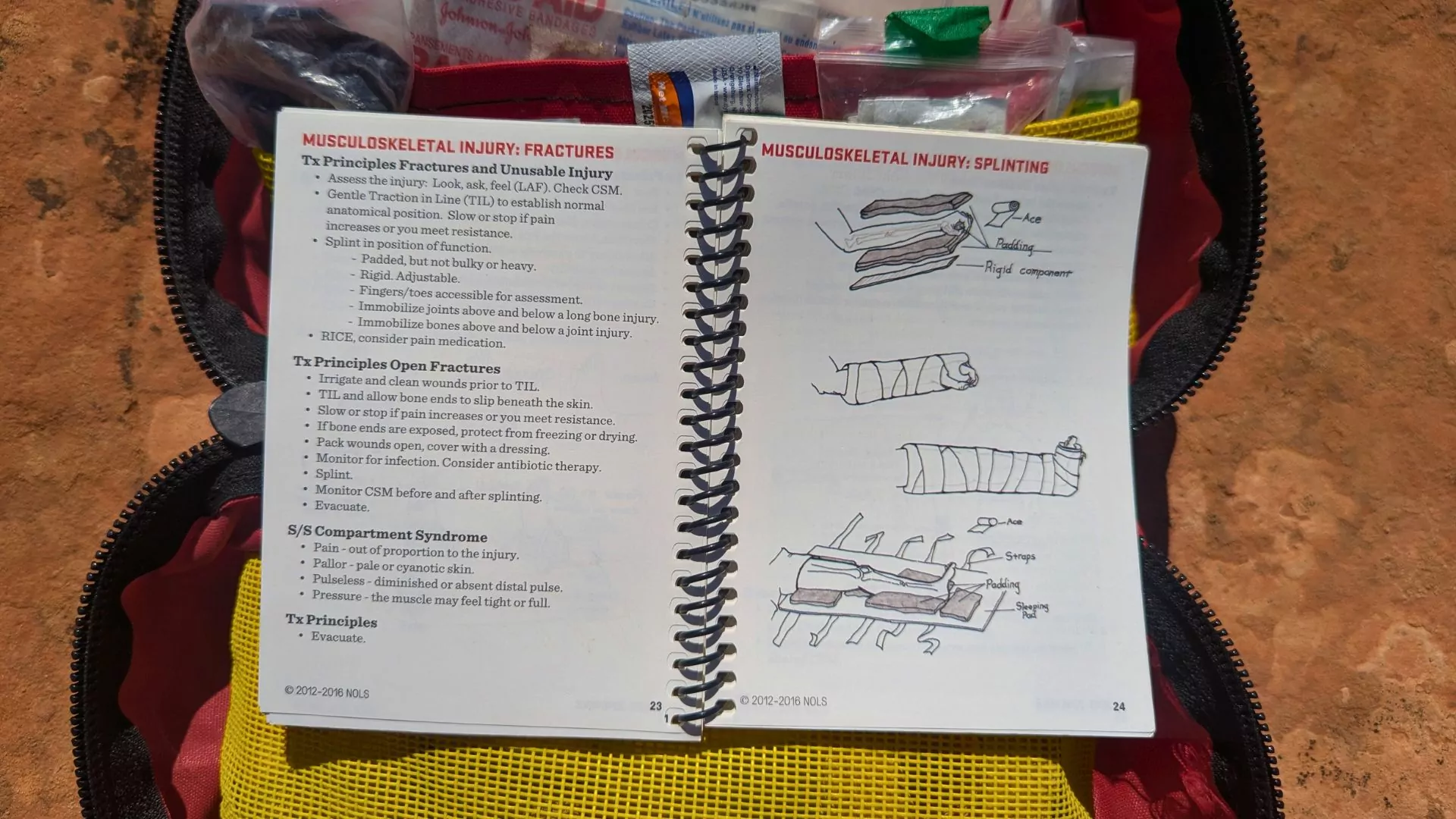

Fractures occur when a bone is broken due to trauma, falls, or excessive force. Symptoms include severe pain, swelling, bruising, and possible deformity. Treatment includes:

- Immobilizing the affected area with a splint or any rigid material available (e.g., trekking poles, sticks)

- Avoiding unnecessary movement of the injured limb

- Applying a cold compress if available to reduce swelling

- Seeking medical help as soon as possible

Sprains

A sprain is the stretching or tearing of ligaments, commonly affecting ankles, wrists, or knees. Symptoms include pain, swelling, and difficulty moving the joint. Treatment follows the RICE method:

- Rest: Keep weight off the injured limb

- Ice: Apply a cold pack to reduce swelling

- Compression: Wrap the area with a bandage for support

- Elevation: Keep the injured limb raised to minimize swelling

Lacerations (Cuts and Wounds)

Cuts and wounds can range from minor scrapes to deep lacerations. Proper treatment helps prevent infection and promotes healing:

- Clean the wound with sterile water or antiseptic wipes

- Apply pressure to stop bleeding using a clean cloth or bandage

- Use a sterile dressing to cover the wound

- Monitor for signs of infection, such as redness, swelling, or pus

READ: Blister Treatment

Hypothermia

Hypothermia occurs when body temperature drops dangerously low. Symptoms include uncontrollable shivering, confusion, and sluggishness. Treatment includes:

- Removing wet clothing

- Providing dry, warm layers

- Offering warm fluids

- Using body heat if necessary

Heat Exhaustion

Heat exhaustion is caused by prolonged exposure to high temperatures and dehydration. Symptoms include dizziness, nausea, and excessive sweating. Treatment involves:

- Moving to a shaded area

- Providing water with electrolytes

- Using cool compresses to lower body temperature

Conclusion

Basic wilderness first aid skills are essential for every hiker, as they provide the knowledge and confidence needed to respond effectively in emergency situations, ultimately increasing safety and well-being in the backcountry. Being prepared to handle a variety of medical emergencies—whether it’s a sprained ankle, a snake bite, or a more serious condition like a heart attack—ensures that you can provide immediate assistance to yourself and others until professional help arrives. By understanding key first aid techniques, such as how to perform CPR, treat wounds, and recognize signs of serious conditions, hikers can prevent minor injuries from escalating into life-threatening situations. These skills not only reduce the risk of complications in remote areas but also help in maintaining a safe, supportive environment for everyone on the trail. Ultimately, knowing basic wilderness first aid allows hikers to act swiftly and with certainty, making them better prepared to handle the unpredictable challenges of the outdoors while ensuring a safer experience for all.